That way, thicket

Preening the tail feathers of an artists’ book

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds

2016

Artists' book, unique state, featuring 15 individual collages on cabinet card with pencil additions, 15 pencil drawings on Fabriano Artistico 640gsm traditional white hot-press paper with metallic paint trim; housed in a Solander box with inlaid collage

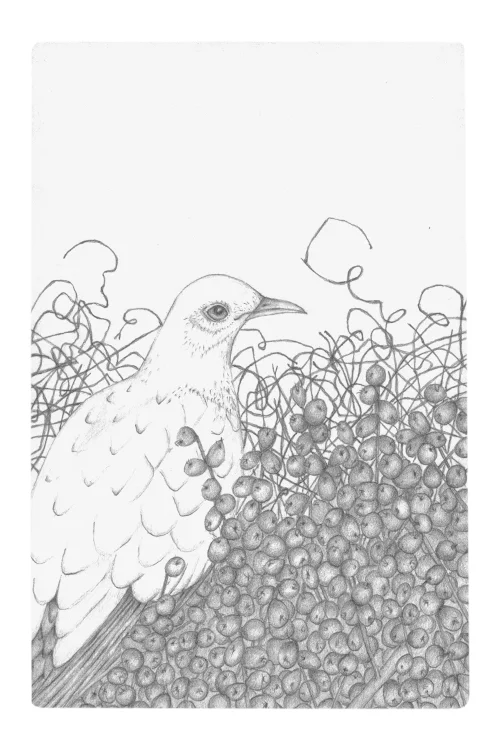

As collages press, and text pages are printed, a closer look at Louise’s silvered and beautiful drawings within our artists' book in celebration of wings and beaks. On this grey spring morning, a chorus of doves awaits.

Superb fairy-wren (Malurus cyaneus)

Splendid fairy-wren (Malurus splendens)

Splendid and Superb, yet still called a herd, a herd of fast-flitting wrens. Splendid and Superb, not only by name, but also by nature. Unfixed on the page, a herd of fast-flitting wrens. With “the grass below” and John Clare’s “vaulted sky” above,[i] they appear without a weight attached. In birder’s thrall, a reminder that “the world was good and it didn’t need me.”[ii] My own part to play is small. I am feather-light and awed before the Splendid and Superb.

Australian king-parrot (Alisterus scapularis)

With a complete red head, the Australian king-parrot blazes. Viewed under ultraviolet light, some feathers even appear to glow yellow — humankinds’ three cone retinas letting me down once more. Clashing with its own spledour, it is largely sedentary and consequently suited to the drawing room. Or so it was thought, until they started to lay their eggs in makeshift beds of decayed wood-dust; a sideboard for a tree hollow just won’t do.

Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

When carved with a pocket knife and emery board an Emu egg, layered ivory through to darkest blue-green, is perfect for the sideboard’s silverware tableau. Handsome silhouettes can be made to dance around the shell merry-go-round, but I favour the movement found in the weaving, bobbing heads of a mob of emus coming my way. With their shaggy plumage, large black beaks for grazing, and wrinkly hose[iii] — New-Holland Cassowary, won’t you come into my parlour? Be my shadow, and play gosling to my Konrad Lorenz.[iv]

Rose-crowned fruit dove (Ptilinopus regina)

Superb fruit dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

The Rose-crowned fruit doves bow their heads, and emit a soft-pitched coo. The Superb fruit dove too. As parson-naturalist Gilbert White (1720–1793) quite rightly penned: “the language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical; little is said, but much is meant and understood.”[v] Their song so sweet, I am obliged to quit my chamber. Us all, untamed, for now, coo coo.

Painted buttonquail (Turnix varius)

From John Latham (1740–1837) naming you the latin for ‘various’ ‘partridge’ to John Gould (1804–1881) borrowing from the Greek for ‘half-foot,’ in reference to your lack of hind toe, a ‘sparkling’ ‘half-foot,’ no less, you’ve answered to many, little Painted buttonquail. Come closer; I’ll not let you stand upon bare limestone.[vi] Come closer; I’ve a garment to fasten, buttonhole-buttonquail.

Torresian imperial pigeon (Ducula spilorrhoa)

The door left open, I hear the soft sounds of the Torresian imperial pigeon — roost awhile, won’t you? This dwelling, this ‘unseasonable heat,’[vii] is not yet our tomb, Mary Shelley, but it is close. Linger with me before you fly off in search of the Marianne North Tree[viii] to the east of the Heartbreak Trail.

Southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

The ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard (1912–1965) in his book, Living Birds of the World (1958), described your feet as being “fitted with a long, straight, murderous nail which can sever an arm or eviscerate an abdomen with ease.” But I prefer to see you in quite a different light. In a garden setting, say. And with pencil and glue, that’s just where you’ll stick. There, adhered, I’ll read to you a little of Margaret Gatty’s talkative trees and cobwebs (Parables of Nature (1893)). And as I ramble on, perhaps you’ll find the chance to make good your escape. Applying your brilliant spatial memory — that way, thicket.

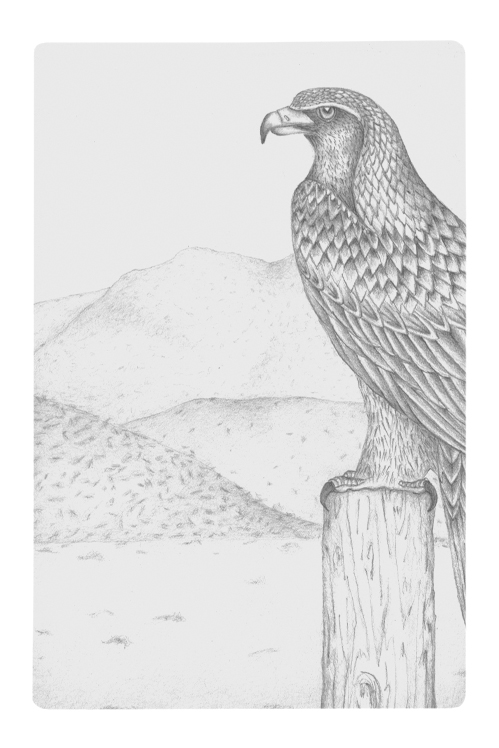

Wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax)

If H is for Hawk, then let E be for Eagle, the largest raptors in the sky above, with wings like long grasping fingers, and pinkish gape. The Wedge-tailed eagle, sharp by name and disposition — continue your depredations! — spies a caged silktail (Lamprolia victoriae) and wonders how it came to be there. A “curious little creature,”[ix] the silktail, shimmied from place amongst the birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae), the Australian robins (Petroicidae), the fairy-wrens (Maluridae), and now here, in the field notes of the hallway. An unexpected diminutive silktail far from home, do my eyes deceive me? As the eagle pipes psee-eew, psee-eew, psee-eew, their conversation is likely to be short.

With strength of wing and clarity of sight, “what we see in the lives of animals are lessons we’ve learned from the world.”[x] With eyes yet to cloud over and wings singed by the edge of the sun, “you too, mankind, are like this.”[xi]

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds in its entirety will be exhibited as part of Birds: Flight paths in Australian Art at Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in December.

Birds: Flight paths in Australian art

2nd December, 2016 – 12th February, 2017

Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery

Civic Reserve, 350 Dunns Road (corner of Mornington-Tyabb Road and Dunns Road), Mornington, Victoria

Brook Andrew; Arthur Boyd; Richard Browne; Penny Byrne; Kate Daw & Stewart Russell; Adrienne Doig; Marian Drew; Juan Ford; Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison; Fiona Hall; Treahna Hamm; Hans Heysen; Patrina Hicks; Judy Holding; Clara Ngala Inkamala; Judith Pungarta Inkamala; James Stu; Leila Jeffreys; Martin King; John William Lewin; Sydney Long; Joseph McGlennon; James Morrison; Munduwalawala; David Noonan; Jill Orr; Trent Parke; Kenny Pittock; Ben Quilty; Kate Rohde; Heather Shimmen; James Smeaton; Valerie Sparks; Henry Steiner; Tjunkaya Tapaya; Claudia Terstappen; Rover Thomas; Christian Thompson; Albert Tucker; Louise Weaver; Guan Wei; Fred Williams; John Wolesley; Salvatore Zofrea

[i] “Untroubling and untroubled where I lie; the grass below — above the vaulted sky,” John Clare, ‘I Am!,’ first published in 1848.

[ii] Tim Dee, The Running Sky (London: Vintage, 2009), p. 15.

[iii] “….stepping warily down the path in dark wrinkled stockings and shabby mini fur coats….,” Chris Wallace-Crabbe, ‘Emus,’ Selected Poems 1956–1994, published 1995, Australian Poetry Library, accessed October 2016.

[iv] Nobel Laureate Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989) studied the behaviour of ‘imprinting’ with a hand-reared brood of goslings who took to him like a foster carer. Lorenz is shown in several photographs with a brood of goslings for a shadow.

[v] Gilbert White, excerpted from ‘Letters to the Hon. Daines Barrington,’ Letter 43, The Natural History of Selborne (London: Penguin Classics, 1995), ed. Richard Mabey, p. 191.

[vi] Sue Taylor, John Gould’s Extinct and Endangered Birds of Australia (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2012), p. 114.

[vii] Mary Shelley, The Last Man, 1826, cited by James C. McKusick, ‘Romanticism and Ecology,’ The Wordsworth Circle, volume 28, no. 3, summer 1997, p. 123, JSTOR, accessed October 2016.

[viii] Botanical artist Marianne North (1830–1890) painted a tall karri tree skirted by a burl in the Warren National Park, near Pemberton. The painting, Karri Gums near the Warren River, West Australia, can be seen in the Marianne North Gallery at Kew Gardens, London, and the tree, to human eyes, appears unchanged by the century and a burl of decades.

[ix] Otto Finsch (1873), On Lamprolia victoriae, a most remarkable Passerine Bird from the Feejee Islands, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, pp. 733–735.

[x] Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk, (London: Random House, 2014), p. 60.

[xi] ‘The Eagle,’ Peterborough Bestiary MS53, early 14th century, cited by Graeme Gibson, The Bedside Book of Birds: An Avian Miscellany (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p. 323.

Image credit: Mt Bruce, Karijini National Park, Western Australia, 2013, by Jo-Anne Blunn