Look closer

Restoring corridors collage workshop with Gracia & Louise

You can help restore a rich biodiverse landscape, one hopeful leap, one leaf at a time

NGV International

180 St Kilda Road, Melbourne

Tuesday 15th of July, 2025

and Wednesday 16th of July, 2025

12–3pm

Awoken during the middle of the night by some sound, some thought, who knows? I looked out the bedroom window and saw the beautiful, familiar profile of a Brushtail possum on the pitch of our roof. He or she was paused on the roof, their head lifted, smelling their surrounds. From my vantage point, against the lightness of the night sky, you could see the illuminated tall crane planted in the massive construction site behind the laneway of houses. Each night, this red, green, and white Christmas tree is in a different placement, near but far, with, depending upon the time and visibility, the flags which hang from its weighted cable, rippling in the wind. Looking at the possum, taking in the view before them, perhaps deciding which way they’ll go next, I thought about how much we ask of our wildlife, particularly in our urban areas and of those who seem so adjustable by necessity to living alongside humans. Possums are remarkably adaptable to living alongside us humans, however I’m sure they’d also like a hollow too. Some more food trees, and canopy to protect them from predators. Against the night sky, and to my sleepy amusement, they assumed the pose of the rooftop Thinker, and I wondered what things looked like from up there. The construction site, in the same block as our home, on our shared back step, is in their home range. It used to be a double storey, vacant factory site, for the past decade or more. Currently it is a deep hole. A deep hole with a Christmas tree crane which points to an imaginary clock face in the sky, two am, three am, four.

Pictured below, moments of winter late, as last night’s Melbourne Chamber Orchestra’s performance of Doreen Carwithen’s Concerto for Piano and Strings, with pianist Aura Go, and Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, in particular, at the Recital Centre, floats in the foreground of awakening in the middle of the night.

Thinking about how wildlife can move safely between one green space to the next, as pockets of green become smaller and increasingly fragmented, of course, leads me nicely to our collage workshop at the NGV.

Wings at the ready! Come fizz in the undergrowth with us, this Tuesday and Wednesday afternoon. It’s free, no booking required, and though tailored for school holiday amusements, it’s suitable for all ages. Come chat about how a pot plant on your windowsill or balcony can support local wildlife? Your green island can be a beacon of hope and provide water, food, shelter, and a meeting point for the tiniest of insects to assemble.

Drop by! Say hi! Drawing upon our Restoring corridors collage, find us amongst the stick insects, caterpillars, butterflies, and beetles in the Great Hall. Come restore important green corridors so that all wildlife, no matter their size, can flourish.

These school holidays join Melbourne-based artists Gracia and Louise in a hands-on workshop exploring restoring corridors for wildlife in urban environments. Guided by the artists, participants will explore environmental themes, the relationship between urban development and wildlife, and the power of art to inspire ecological change. If you are curious about the intersection of art and nature, this collage-making workshop promises to be both thought-provoking and a visually engaging experience.

— NGV

In addition to workshop preparations, we’ve been working on a couple of new things, also winged and soon to be revealed.

It was an absolute privilege and illumination to talk with Dr Ken Walker, Senior Curator of Entomology, Museums Victoria Research Institute, about the brilliance of Mutillidae recently. We rendered ourselves Alice through the Looking Glass wasp-sized, as we peered at a female Velvet ant writ large on the screen. And she peered back at us, a dimorphic beauty of a specimen, collected in 1963, in all her armoured glory. A montage of 50 frames, every one razor sharp, revealed her amber glass thorax with striations, her GPS-like lens atop her head, which allows her to see in ultraviolet and polarised light, her compound eyes that allow her to see in a level of detail we’ll ever struggle to fathom — 300 frames per second! Imagine that!? I move in slow motion, comparatively. Wasps, evolutionary speaking, so, so far advanced, compared to ourselves. This awe we feel for them, we keep endeavouring to funnel it into our next thing growing.

In the above sweep, can you find the oldest specimen in the collection, from China, 1742?

What can we do to help bees?

One of Ken’s roles as a scientist is to map out where these native bees occur. ‘Until you know where an animal occurs, you don’t know how to protect it,’ he says. And, like many Australian native animals, the threat to bees comes largely from human activity.

Urbanisation, agriculture, and pesticides are all bad news for insect populations. ‘Insects are the mainstay of almost all ecosystems in the world,’ says Ken. ‘If you remove the insects then suddenly everything above it will collapse.’ Which is bad news for us.

And Ken singles out neonicotinoid pesticides, or neonics, as one of the biggest risks to bee populations. Once sprayed on a plant, neonics are absorbed into every part of it — which is what makes it so effective. ‘Any insect that eats part of the plant gets affected by it,’ says Ken. So, if a bee eats the pollen from one of these plants it also ingests a neurotoxin that permanently binds to and destroys its nerve cells. These pesticides were banned by the European Union in 2018, but they are still readily available in Australia.

Widescale land clearing is also a problem for bees, in that they need corridors of flowering plants to sustain their movement.

— ‘From A to Bee: Australian bees need our help, but which ones?’, Museums Victoria

Reel, launched in July 2020, featuring variations of our original works on paper and large scale collages in a different format, a continuous digital reel, will be retiring this month. Having run for five years, it will still exist as an archive of sorts.

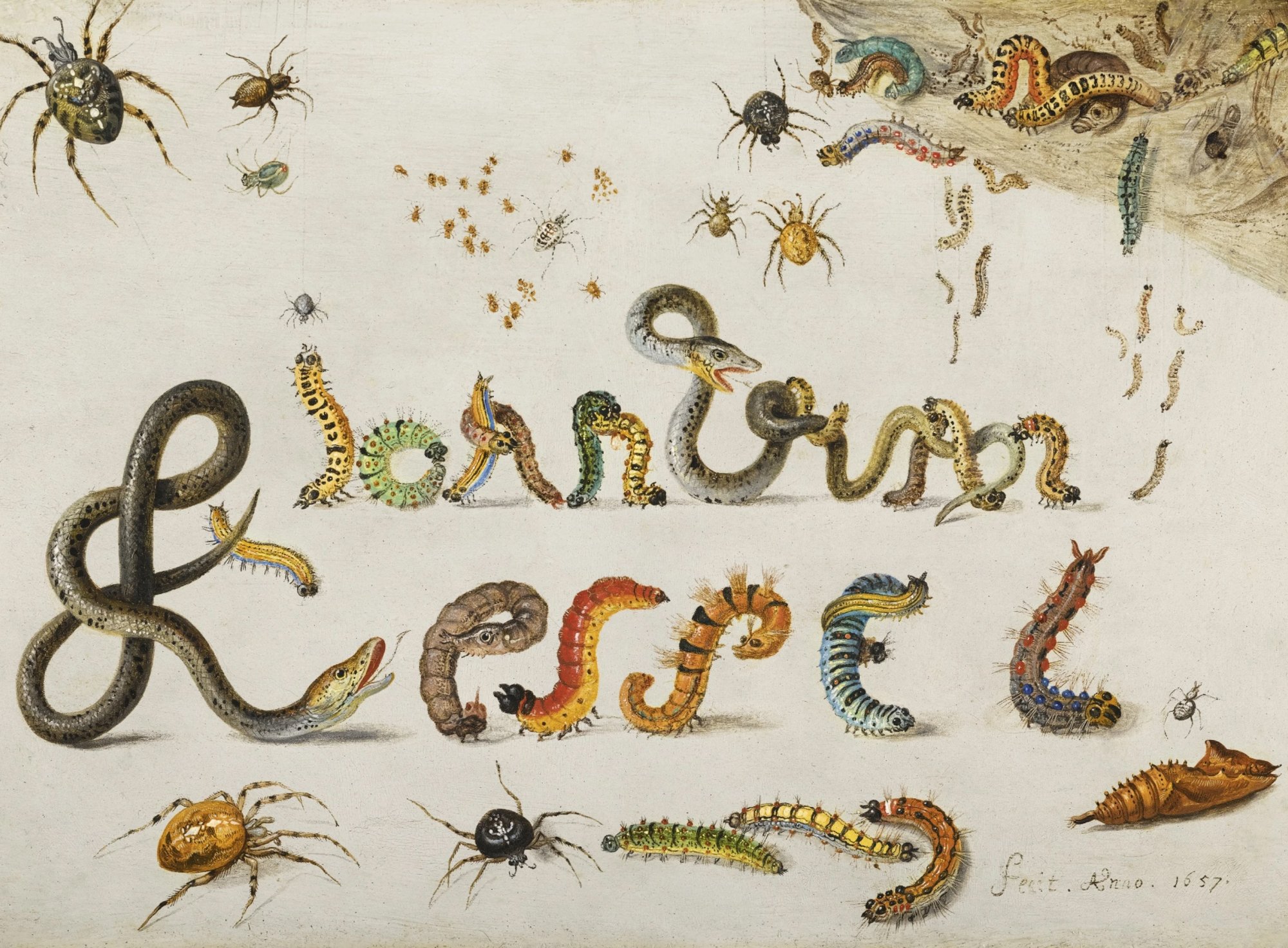

Image credit: Jan Van Kessel the Elder, Garden and house spiders with grass snakes and caterpillars contorted and entwined to spell the artist's name; A sprig of redcurrants with an elephant hawk moth, a ladybird, a millipede and other insects, one signed centre (with the bugs and animals): JoAn vAn/ Kessel and dated lower right: Fecit. Anno. 1657 .

Sotherby’s catalogue note: Jan van Kessel’s intimate cabinet paintings, which combine a minute observation of nature with a wonderfully decorative design, have always been the most prized of his works. Perfectly exemplifying the spirit of the age of enquiry from which they stem, and reflecting the recent invention of magnification that allowed the miniature to be examined and admired in detail, they are all inventive, hyper-realist, and wonderfully attractive; the copper panel comprising one of this pair of pictures however, in which Van Kessel has spelled out his name with a variety of grass snakes and caterpillars, is unquestionably the most innovative of all.

In it a plethora of caterpillars, large and small, real and imaginary, worm their way out of an earthy corner into the picture itself, contorting and arranging themselves around and precariously close to a hungry-looking grass snake, to honour their creator by spelling out his name. Van Kessel's celebration of his own name writ-large in bugs is not however an act of self-aggrandisement; it is rather a witty and self deprecating jeux d'esprit, its humour emphasised by the miniscule Fecit and date that follow in the lower right corner.