A whisker of light

Looped

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Presented in partnership with State Library Victoria

4th August – 26th November, 2017

La Trobe Reading Room

State Library Victoria

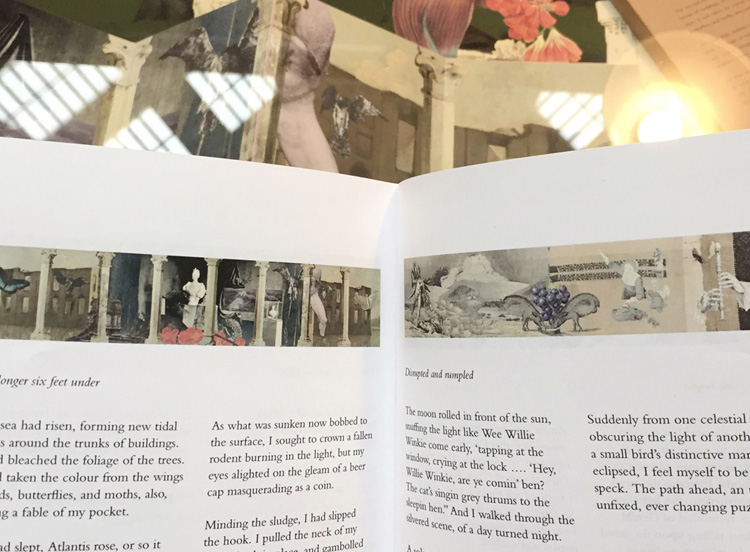

Looped is bound by a short tale, A whisker lighter.

Crick, crack, snap back. I arrived early at the office and opened the window, inviting the city inside. Rarely unlatched, with its mouth caught in an inward folding yawn, the window inhaled the pollen of the plane trees, and threatened to sneeze to a close in the wind.

Once a ballroom, the office was now a shabby knot of furniture and unpacked cardboard boxes with random piles of paper and books and overflowing rubbish bins. The tall window hinted at the original glory of the building, and had the ability of being able to draw the outside world under its wing while keeping it at a distance. The purr of traffic filled the room and sank into a painting hanging from one nail in the wall, askew.

Through the window came not just dust and noise to layer the scene, but sometimes the odd sparrow as well. In they would hop, and finding the interior world not attuned to their needs, out they would hop. Looking at the outside ledge, I noted that someone had installed plastic anti-pigeon guards. I collected the two flimsy strips and tucked them beneath my desk as the rattle and whir of W and Z class trams sliced the streets below.

The room hummed and I with it. I looked up at the sleeping ceiling rose held between a grid of fluorescent-tube lighting, and let my mind wander. What was once a beautiful space of possibilities was now a slouched grey institute. No pigeon, nor sparrow, was likely to call today. More’s the pity.

One, two, as the office filled, the large window was shut. The computer monitors tipped their heads forward, as the latches were fastened. Do you mind; it’s my allergies. No, of course, please do. Polite, light-hearted, banter. The air-conditioner, the click-clack of keys, and chitchat diluted the sounds of the street, returning the distractions of the city to their place, out there, keep it shut. File, save. Continue. Someone talked about the different types of cheese, and their youthful days spent shooting hoops. Wildly disjointed, like the current drab character of the room, overheard talk of what had been and was no more added a spitball of fromage to the faded grandeur. All was meaningless, turned inward, and I fell away. Vanished.

In my head, I packed up my belongings. Slid my phone into my bag, refolded my papers along their seams and slipped them inside the sleeve of my notebook. Think I’ll go out and walk. Stretch my legs. All this sitting, it does me no good. My knees are hot, and my hips ache. This chair is tailored to someone else’s measurements, to an every-person who doesn’t exist. Besides, it’s sunny out, and cold in here, underneath the air-con. I rubbed my hands together to bring back their circulation. I undertook a little fake typing as I heard the tread of my boss in the hallway, enjoying the false rhythm of my words and the line of nonsense on the screen. Whersdd fdgss fsdf gfercskoa dfer rsds. Tools, Spelling and Grammar, Change. Just as soon as they go for coffee, I’ll nip out. Just for a bit, my movements announced. Just for a spell. Need to clear my head. A quick saunter: a chance to rest my mask. The impression of quietly working was taxing. Clackity-clack, paper shuffle.

Quickly, quickly, down the stairs at a canter, and out onto the street, I slipped into the crowd, following its motion. Swept forward in the direction of the soulless lunch halls, juice bars, and tiny cafés, I was the flipside of a flâneur with no room to saunter. But cobwebs could still be un-tacked and joints oiled in the rolling swell; I could still dissolve into my own world; disappear inside a crowd. Giving myself over to just walking, one foot in front of the other, until I found my longed-for beat. Turn right, ahead, pause, turn left, ahead. Walking with purpose and a steady pace to an imaginary appointment. Don’t move too slowly, mind. Just ‘make yourself invisible, or get busy with something’, advised the forever-walking words of Robert Walser in my ear.

There, at the tram stop, a beige of commuters. With their phones they could shut out the disturbances of other people around them. They could look important, interesting, disinterested, don’t bother me. They could be as hidden in their focus as they chose. It seemed that no-one noticed anybody anymore, and, of course, this was particularly advantageous to me; from not just the sidelines, but out in the middle, I could watch the quirks and patterns of others. Thanks to the handheld device, the twitcher in me no longer needed a bird hide in order to observe my subject. Make yourself invisible, or get busy with something. Would anyone look up if I pulled a face in spite of the wind?

Passing the library, a sizeable section of the lawn was fenced off. A low temporary barrier had been pegged in place to enable the grass its forty-winks to regenerate. A kip to allow the new seed to take hold seemed just what I needed also. And there, atop the bed of sleeping grass, a kit of pigeons, a flock of gulls, and a quarrel of sparrows with no desire to call in on the old ballroom when they had such a prize. Safe, and in possession of a sheltered location, they basked in the warmth of the sun. The pigeons, in particular, puffed out and fanned their feathers to make the most of the solar heat. Their fans lent the scene an air of Sunday picnickers, an Eden for Birds Only, and I was glad I had chanced upon this moment that threw sunlight on my impression of the world. It was in these small and ephemeral shards that life made sense. All that was good, transfigured into form! It was in these quiet encounters that I was pierced and purpose was found.

When I walked, my pain was dimmed.

I headed down the street, and turning left, noticed a man dragging a small dog behind him. The dog could barely keep up with the man. He looked tired, as if he’d been walking for hours. But he kept looking up at the man, rather adoringly. And the man would occasionally return his gaze, and look down at the dog with something akin to love. On they walked, the man, quickly, on long legs, and the dog wearily scampering behind him the way a puppy does. The dog’s collar looked heavy and the lead and connection were too large for its frame. It in turn filled me with heaviness, as I trailed behind them.

Those earlier light lances that had pierced the forest canopy, faded. I forgot the pleasure I had drawn from the sunning birds and their prime real estate. The contrast in states was a slap to my cheek.

As the dog kept pulling over to sniff the corners of buildings and discarded food wrappers, his whole body appeared to pause only to be yanked along by the man. Keep up. Come on. Witnessing a small moment of everyday cruelty tore at my heart. There was perhaps no malice, but there was no understanding either. There was no compassion. I quickened my pace so as not to lose sight of them in the stream. A sort of silent urban camaraderie between the dog with its tongue lolling in its mouth and me, but I didn’t dare say anything. I didn’t say anything at all. And for that I felt ashamed. Your dog is thirsty. Your dog is tired. That collar and lead, they are too heavy for such a small dog.

A little ahead of me now, the dog drank from the dirty pool of rainwater in the gutter, and my shame grew. Soon I would have to abandon the role of shadow and pass them, keep going. And keep going I did, leaving the dog to stand up to its owner. A useless lump rose in my throat. You can do as you please, out in the open. It was in such unassuming tragedies, my part included, that any meaning recently found was lost. Guilt gnawed at my collar and made a roost about my shoulder. I walked on, but found it would not be shook. The city grew louder. Harsher. Faster. Sour. Suck it up. Walk on. Hide your heart.

Why can’t you tell lies to yourself?

My feet headed to the gallery. Up the stairs, to the permanent collection, seeking a place I would often sit when I had nowhere in particular to go. I sought out the familiar. I headed past the heroic actions in verdant landscapes, and bronze statuettes in a considered knot. I heard the rustle of aristocracy in satin and fur as they rested their tiny slippered-feet upon skulls and clouds. Through the well-populated grand rooms, one by one, until I reached my public-private nook where the ceiling was in closer conversation with the floor. There, nestled in a quiet arrangement of noted furniture and ornaments, she sat, too, a woman holding a black cat, in the form of Gwen John’s painting, Young Woman Holding a Black Cat (c. 1920–5).[i]

Just like my familiar walks taken from my desk, John also retraced her steps and created many versions of the same composition: small oil paintings of solitary women shown in three-quarter length. From the label, I reread how the sitter, who frequently sat for the artist, has remained unknown by name. She was merely recorded as the “Convalescent”, and for my needs, that seemed fitting. I was a convalescent, in the gallery. My illness had outstayed its welcome, both in so far as I was concerned, and those around me. Perhaps this had also been the case for the sitter too. We had both of us worn out their concerns. Most people stopped asking how I was faring. Maybe it was because they’d heard my answers before, because it made them uncomfortable, because it was without an end? An ongoing condition? Oh no! That won’t do. How tedious. It’s chilly out, but nice if you are standing in the sun.

Returning to the known comfort of the wall plaque, I was re-informed of what I had forgotten: the painting was created in John’s apartment in Meudon, France, and discovered hidden in the attic after her death. But the label needn’t remind me of what drew me first to the work and what I had already sensed: John loved solitude; John loved cats. To her, and to me, a cat was ‘an affair of volumes’,[ii] unspoken.

Looking at the painting quietened me. Like walking, it was sometimes capable of pushing the difficult thoughts aside. In the portrait, I recognised myself. Not my particulars, but me, all the same. It was not a mirror, yet it was an extension of me, with hands wrapped around the velvety mosaic contours of a cat. Canopy cleared. She, I, we appeared the embodiment of John’s own ‘Rules to Keep the World Away’.[iii] She, I, we will find a way to voice concern for a dog in need of a drink. Next time, she, I, we will not hold ourselves invisible.

And inside, I felt happy. Worn out, crumpled, yes to both, but, restored. I left the gallery, and headed slowly home to my beloved cat. We all needed a fixed point, I thought.

Crick, crack, snap back.

Someone opened the window behind me, waking me from my mind. For a moment there, time had been a familiar walk. Minutes had translated into a ramble. A postcard depicting Young Woman Holding a Black Cat fluttered from the shelf and landed upon my keyboard. I glanced at the resting screen, nudged the mouse, and noted the time. Inward, outward, all the same, but a whisker lighter. Soon it would be time to rise from my desk and head home to my own beloved cat.

Yes, we all needed a fixed point.

[i] Gwen John, Young Woman Holding a Black Cat, c.1920–5, oil paint on canvas, 460 x 298 x 17 mm, in the collection of the Tate, U.K., purchased in 1946 and currently not on display.

[ii] Cecily Langdale, Gwen John: With a Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings and a Selection of the Drawings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987) p. 1.

[iii] ‘Rules to Keep the World Away: Do not listen to people (more than is necessary); Do not look at people (ditto); Have as little intercourse with people as possible; When you come into contact with people, talk as little a possible ....’, Gwen John (1876–1939), 3rd March, 1912.

You can pick up a copy of this short tale in zine format from the dais in the La Trobe Reading Room. Our free Looped zine also includes the details of the artists’ books within each of the cabinets. And please feel free to share your photos of the work with the #GraciaLouiseLooped hash tag.

Looped is a satellite show to Self-made: zines and artist books, of which our work is also a part of, in the Blue Rotunda, Cowen Gallery, State Library Victoria, until the 12th of November, 2017.

Image credit: Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison, Looped, 2017, on display at State Library Victoria