In the wings

A velvet ant, a flower and a bird

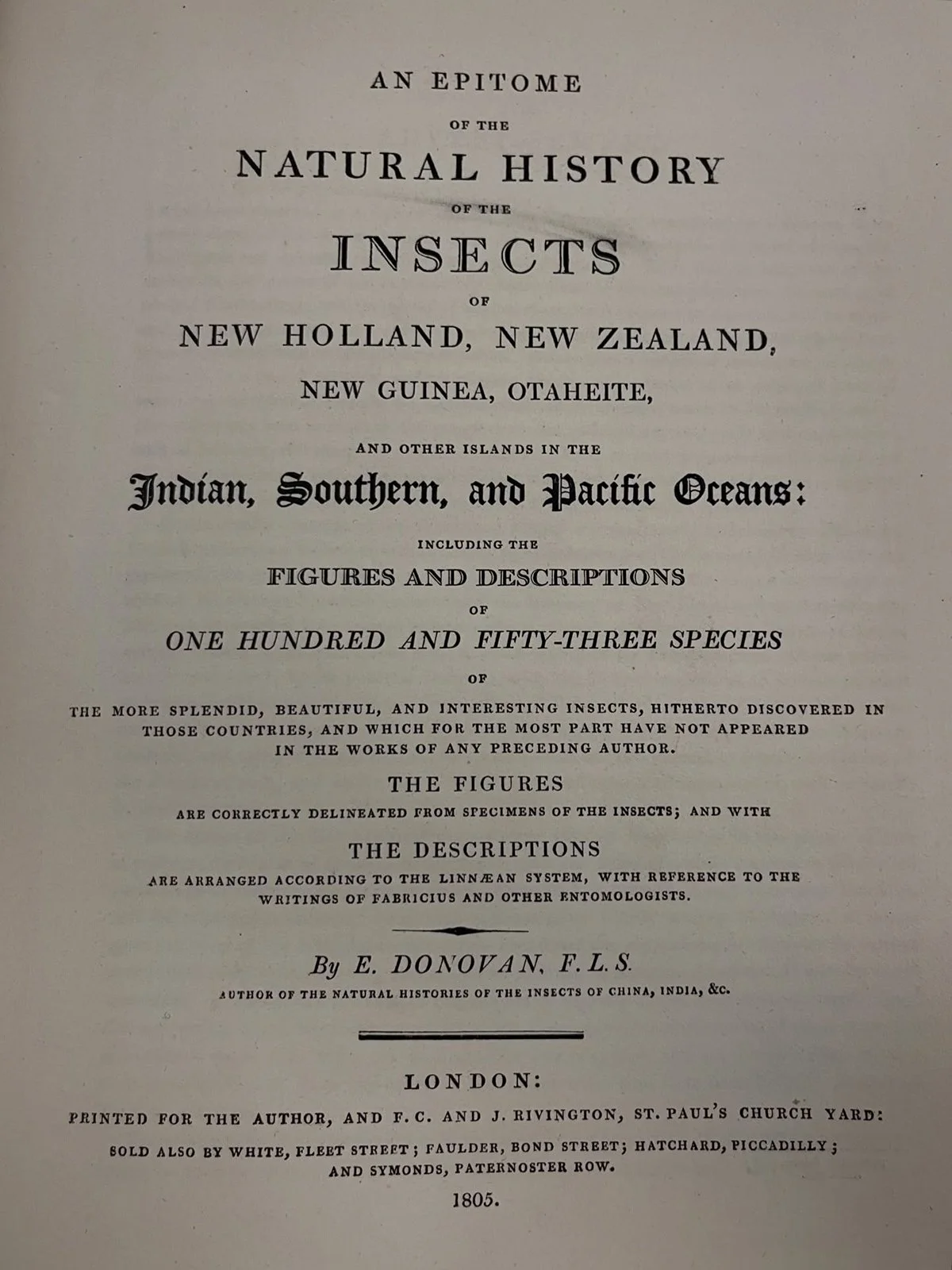

A Potter Museum of Art commission for A Velvet ant, a flower and a bird exhibition guest curated by Professor Dr Chus Martínez, Head of the Institute of Art Gender Nature at the FHNW Academy of Arts and Design, Basel, Switzerland

Potter Museum of Art, Cnr of Swanston Street and Masson Road, Parkville

Thursday 19th of February – Saturday 6th of June, 2026

“The insect’s principal task in navigation

is the retention of consecutive dead-reckoning summaries. For example, during an ant’s foraging run its brain has to compute all the angles the animal has turned and all the distances it has traversed and to integrate all these vectors continuously. It is on the basis of such continuous integration that the brain is able to calculate the heading enabling the ant to return to its nest on a straight line from any point on its foraging course.”

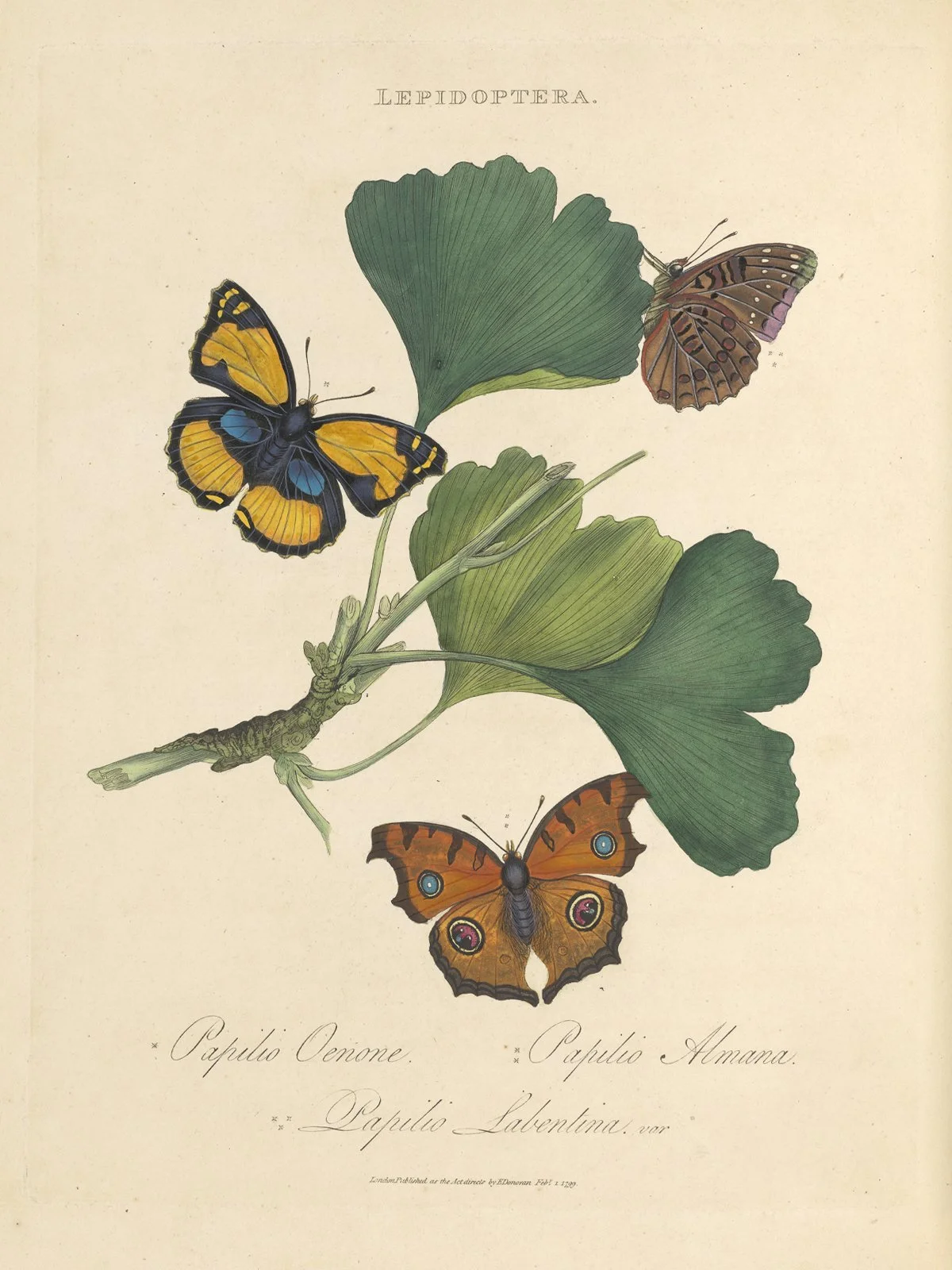

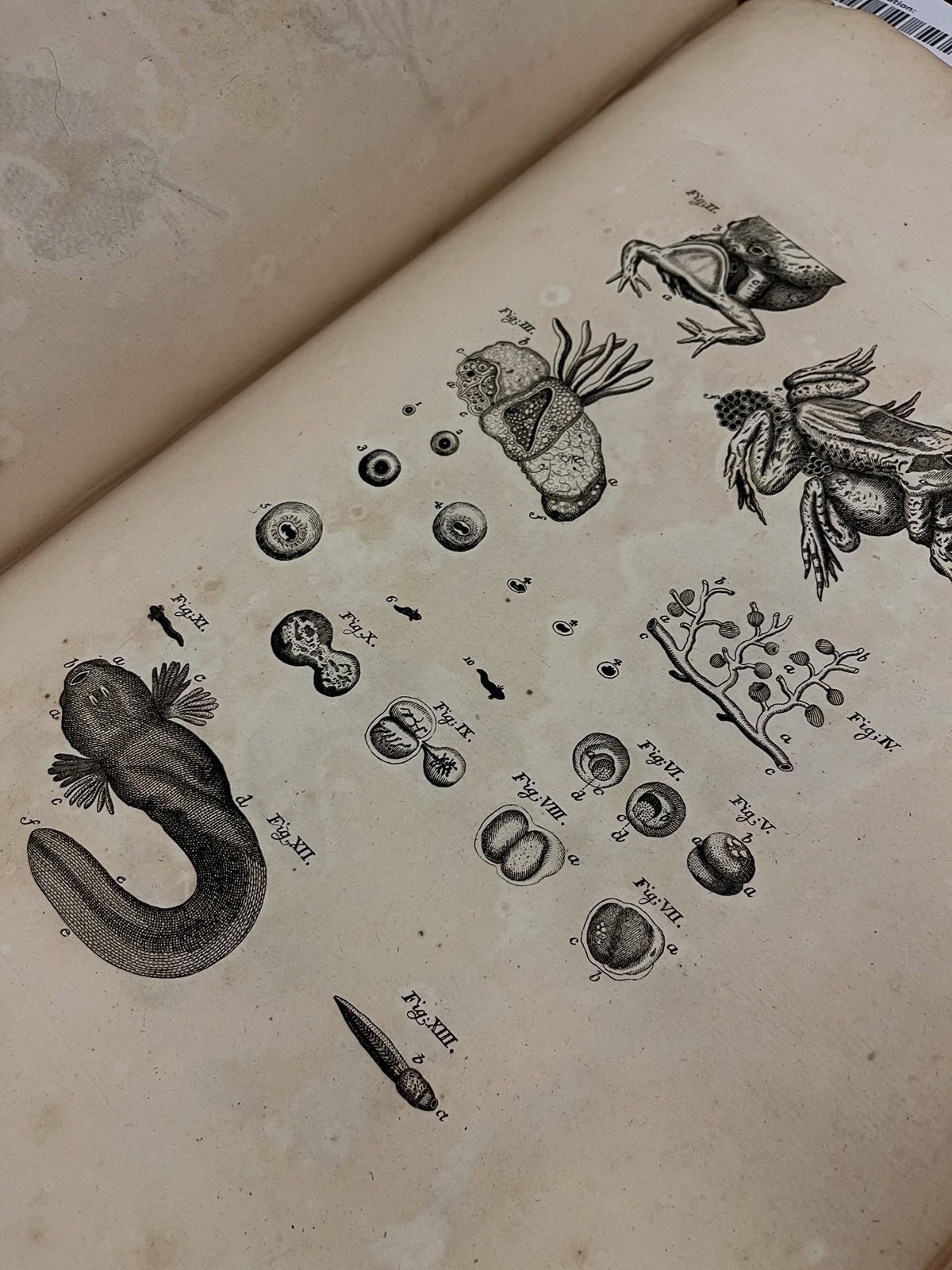

In our work, celebrating the intelligence of the Velvet ant, a female mutillidae, we hope the small writ large encourages people to consider what the Velvet ant might see, as she searches for a host’s nest in which to lay her single egg. Of course, we can never know what she might see, nor what it is like to read the world through polarised light. She is small, compared to us, and her life is also deemed small, again, compared to us. But is she? And is it? Or are we still seeing as human? She is unfathomable in her enormity of knowledge. She selects a host’s larvae in relation to the gender of her egg: a larger host species is located for a female, a smaller one for a male. With her unique defence mechanisms and parasitic behaviours, the Velvet ant is mighty.

We need new ways of determining intelligence that is not centred around human. Her human-ascribed common name alone refers to her as being another species, an ant. This says so very much.

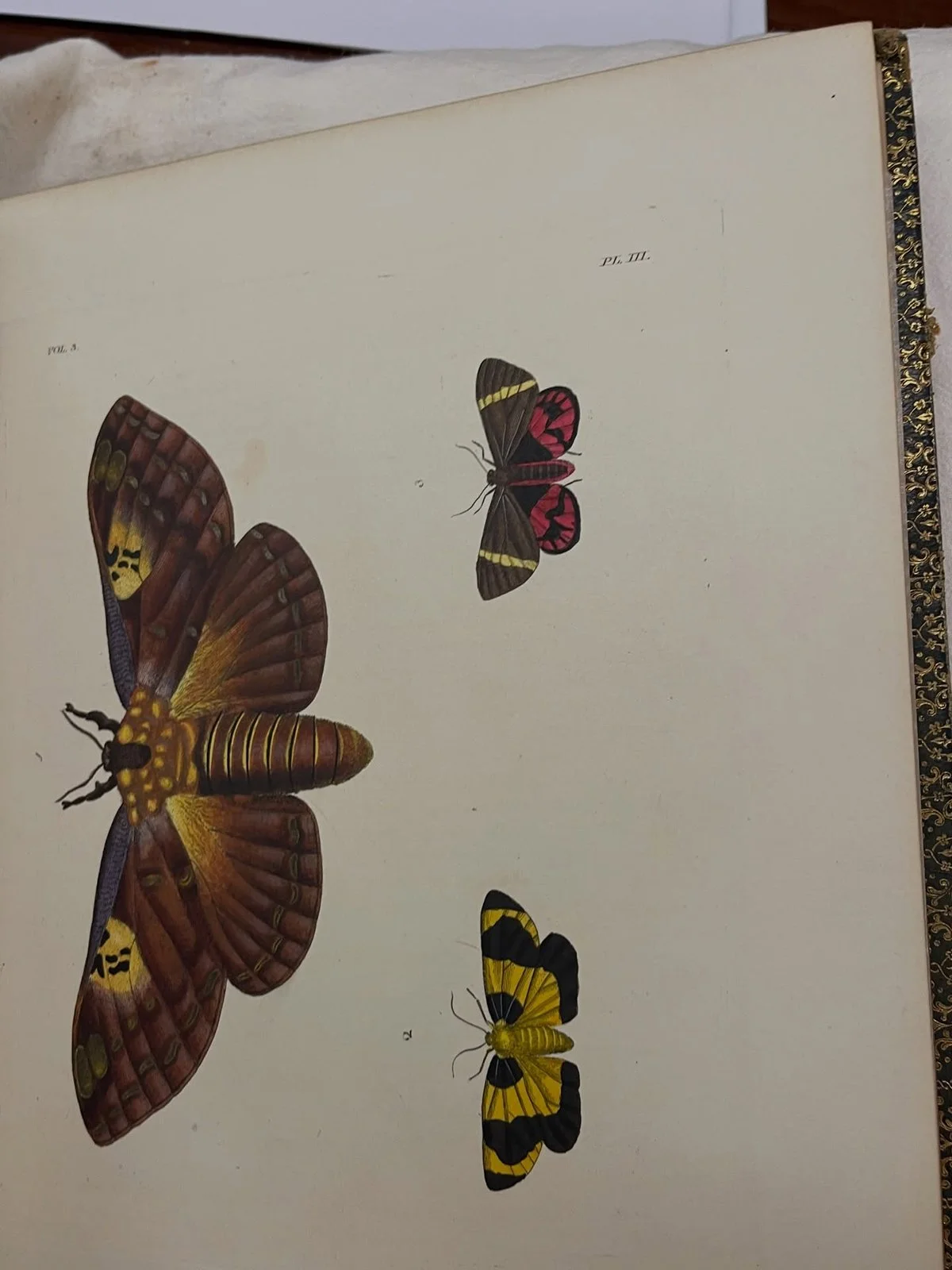

How we measure intelligence in animals (typically through self-awareness mirror recognition and complex problem-solving tests) is limited. The markers of human-determined intelligence pertain to our abilities and interests, our definitions of success and what is deemed worthwhile (by some, not all). So, we are perhaps not just asking, what does the world of a Velvet ant look like, but what can we learn from seeing the world as another species might? How else does intelligence manifest? How does the female Velvet ant know the gender of her egg? How does a bee feel, and accordingly interpret through their imagination, an object in the dark? How do Monarch butterflies pass their migration pattens on to their offspring?

All too often we view the world in relation to ourselves. Turn that around, shift your spatial cognition within the animal kin-dom. See the world through the vantage of another and be not just awed but learn. Through knowledge and compassion, new realms emerge. Failure to recognise, and consider, animal intelligence diminishes the beautiful interwoven whole.

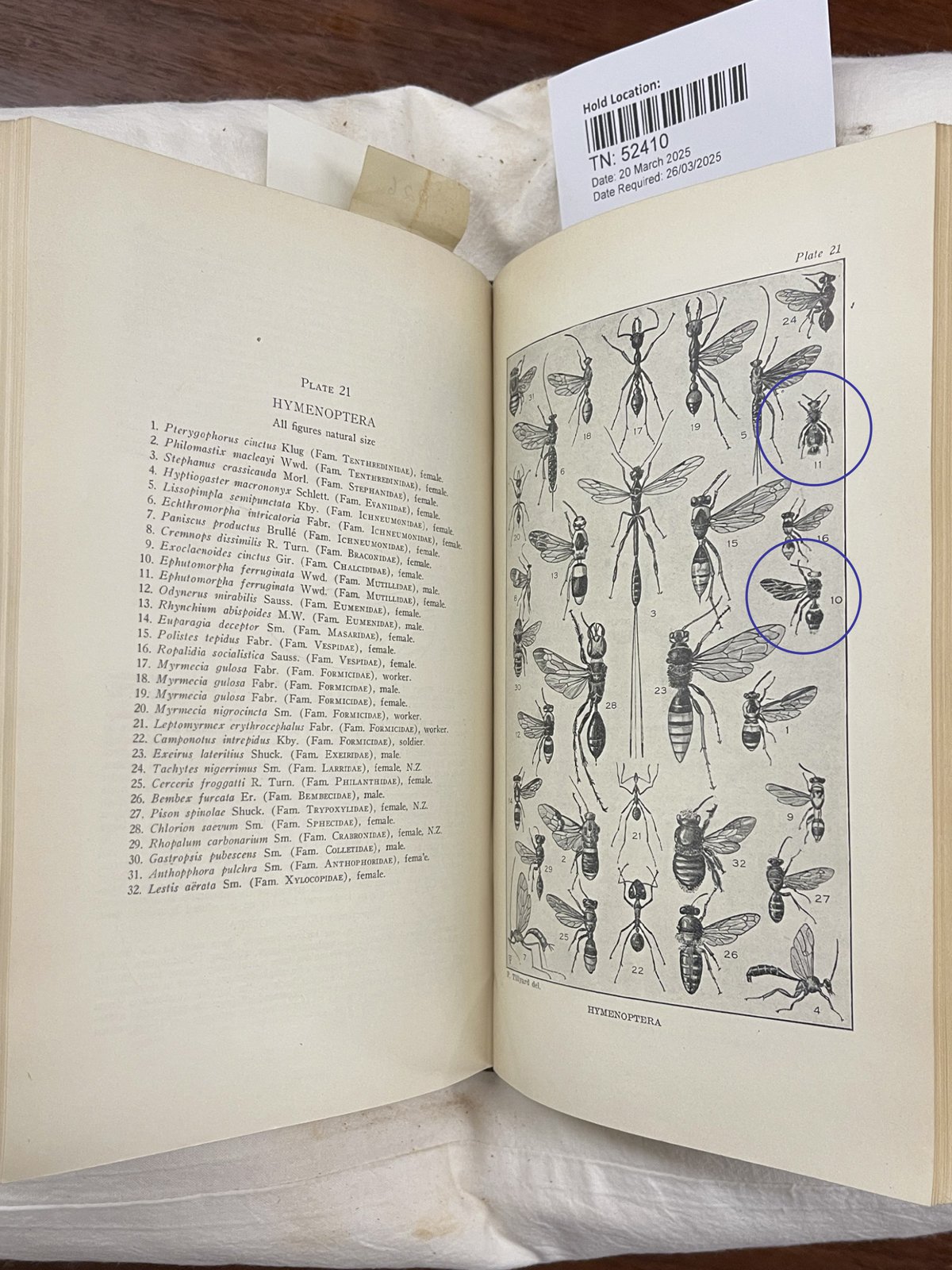

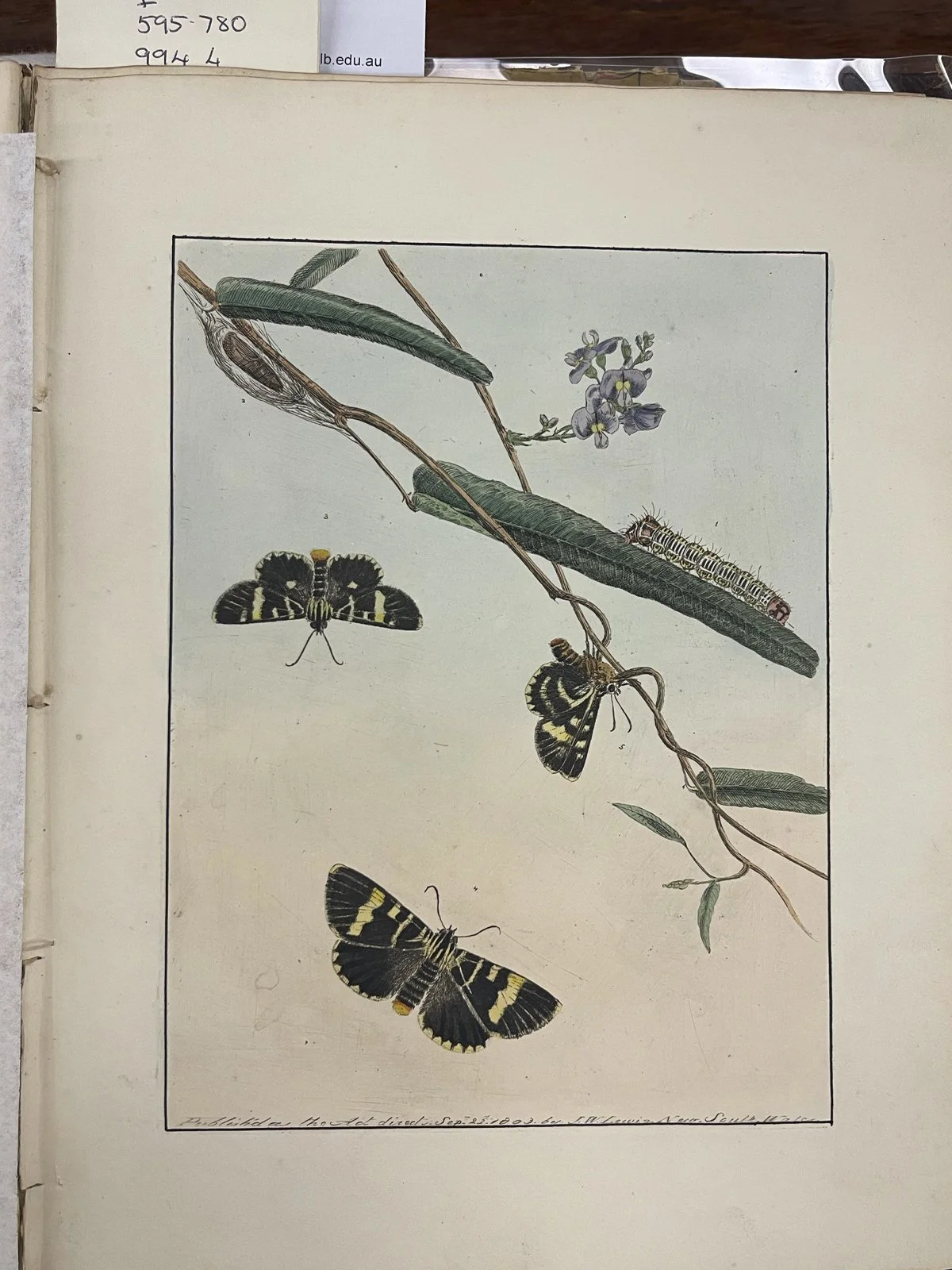

(In the second image, below, circled (digitally), you can see the female and the male Velvet ant in an edition of R. J. Tilyard’s The insects of Australia and New Zealand, 1926.)

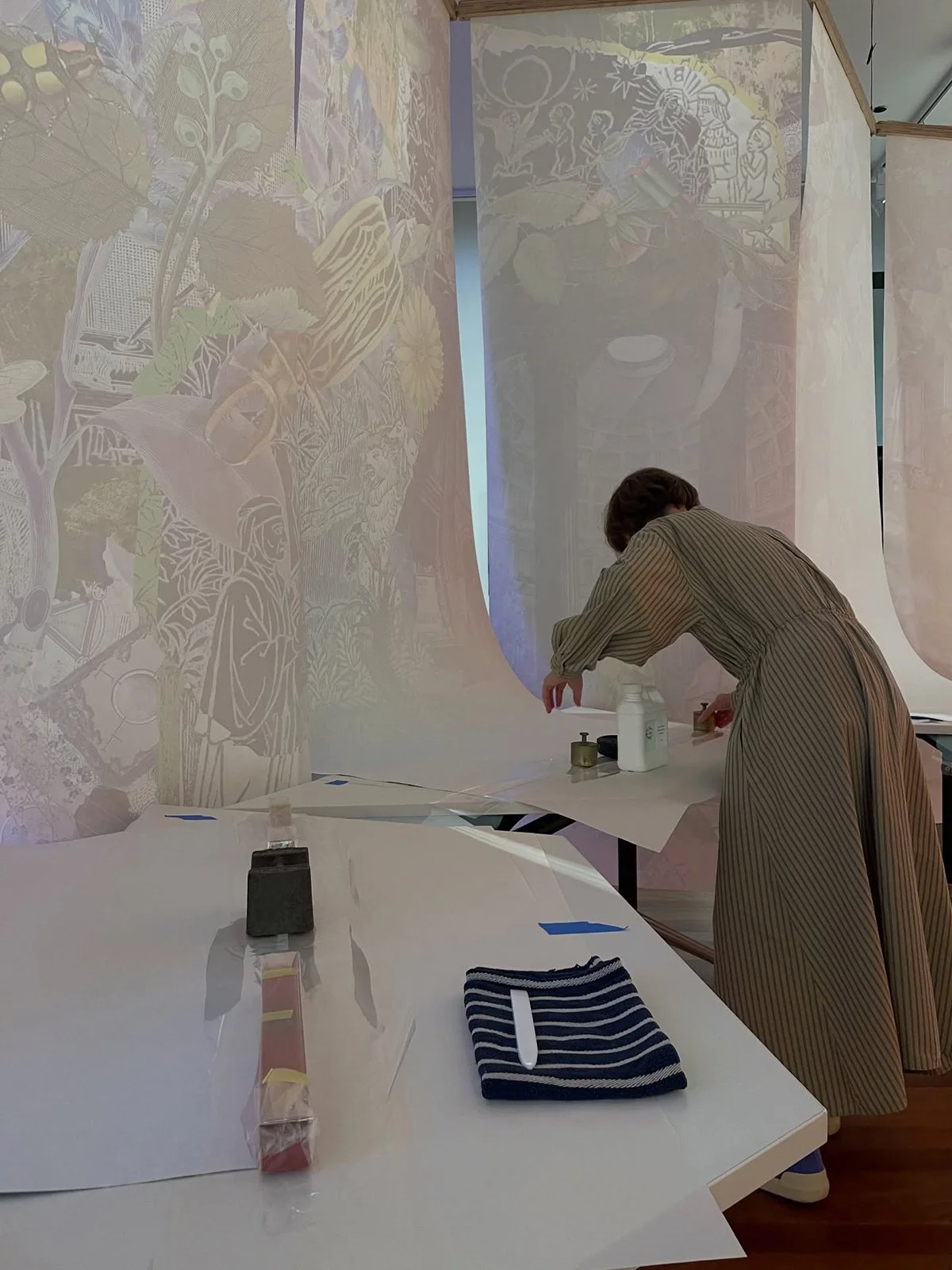

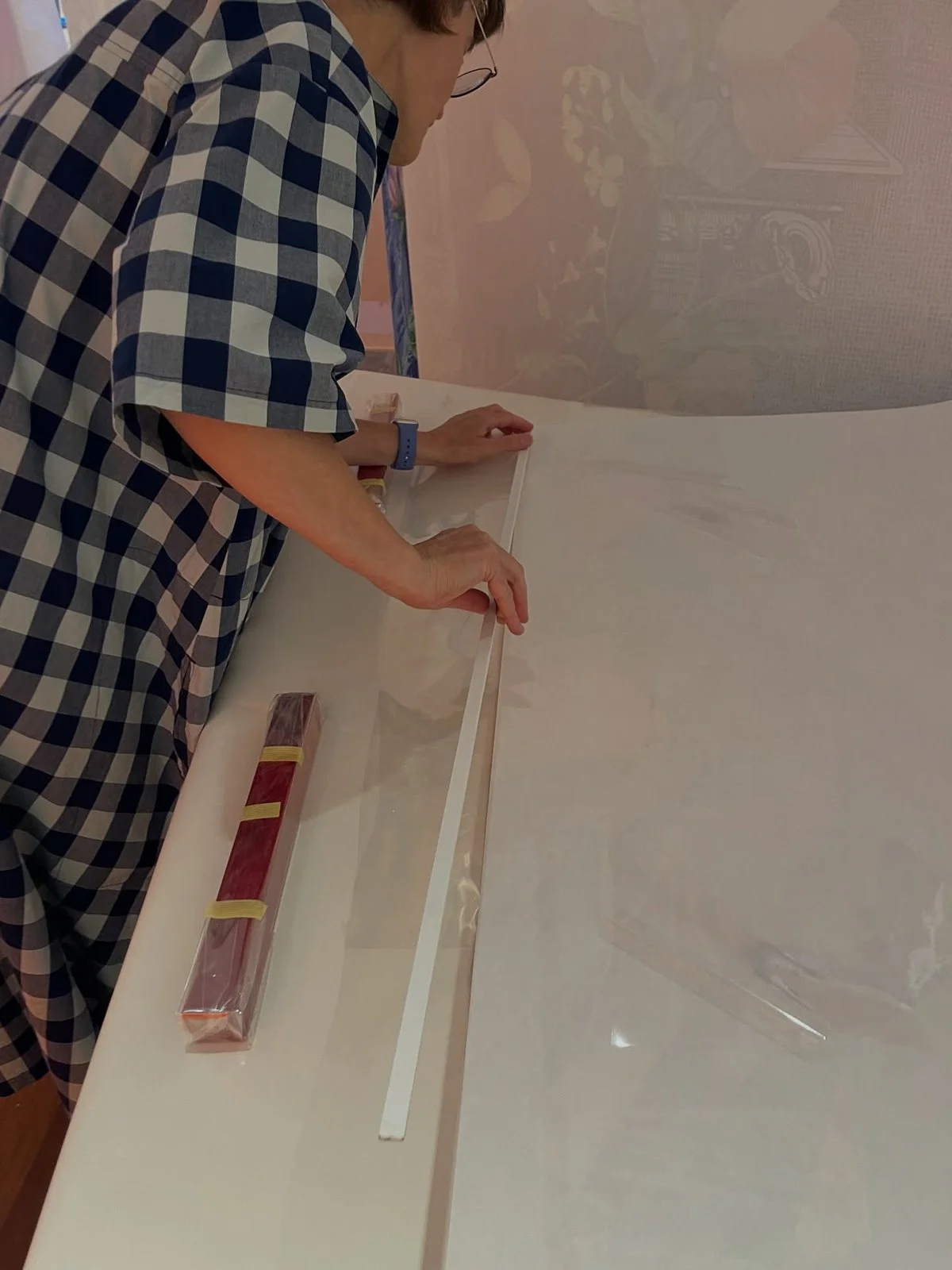

“It is funny, there is almost no humidity in Melbourne and even less inside the Museum and yet the wonderfully textured Japanese paper that gives its body to the work of Gracia & Louise absorbed the water on air and bent”

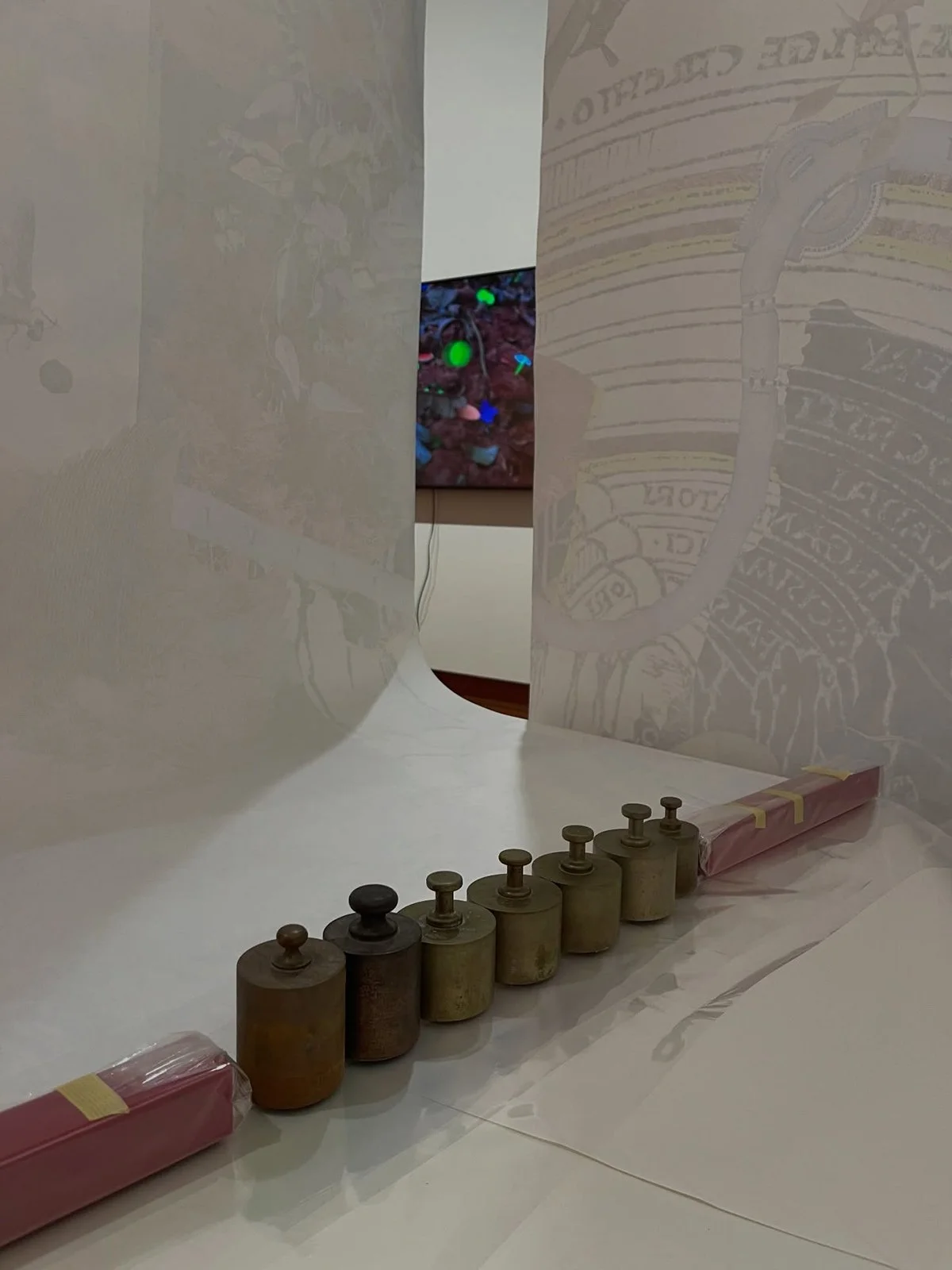

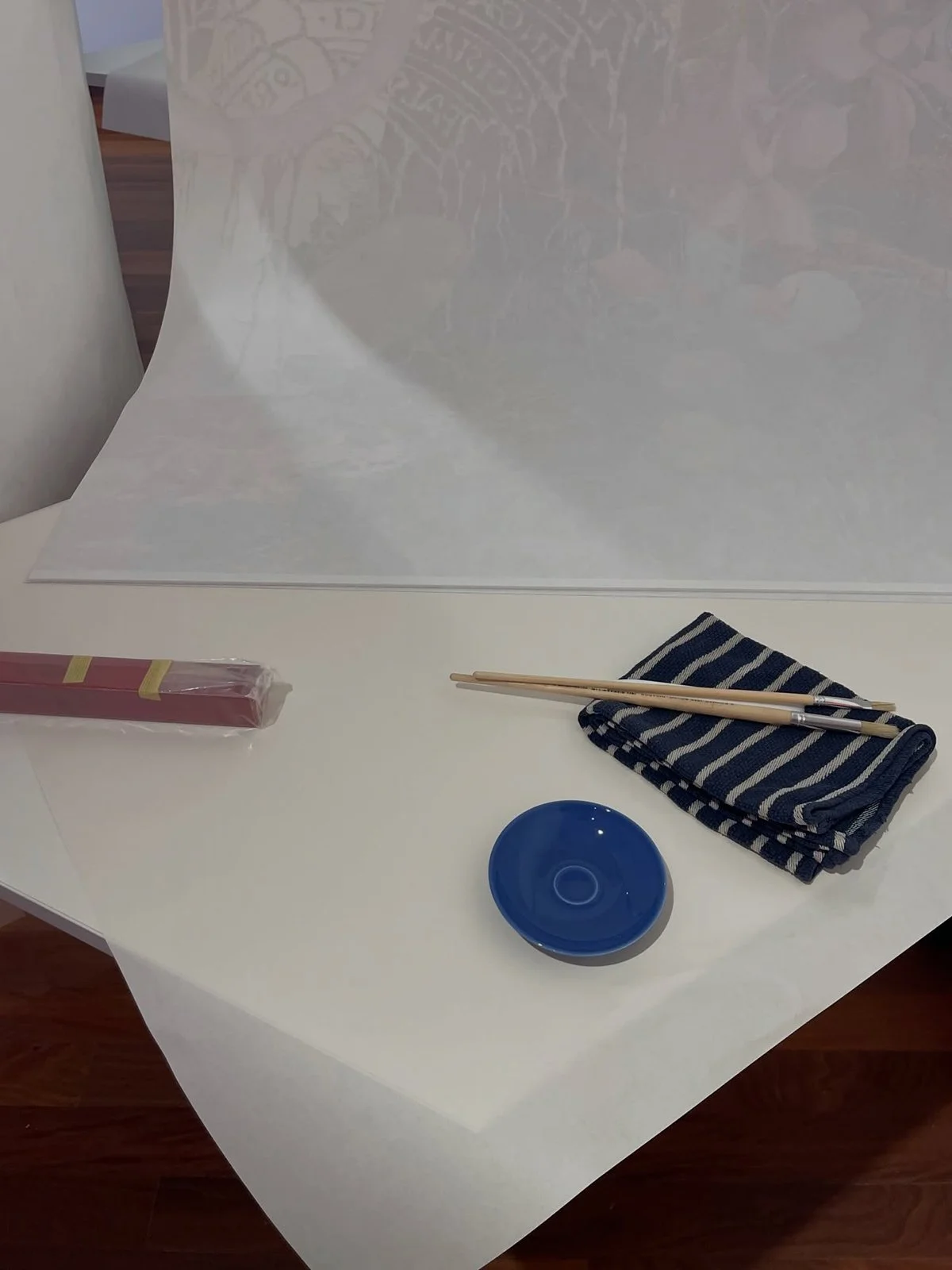

When disturbed, the female Velvet ant makes a squeaking or chirping sound through rubbing her abdominal segments together, signalling an auditory warning. In much the same way, our artwork, disturbed by the humidity, issued a distress call. All calls heeded, we’ve given her some extra support at the tail. Fine batons, each one metre in length and encased in Moenkopi Kozo paper sleeves, now offer their assistance.

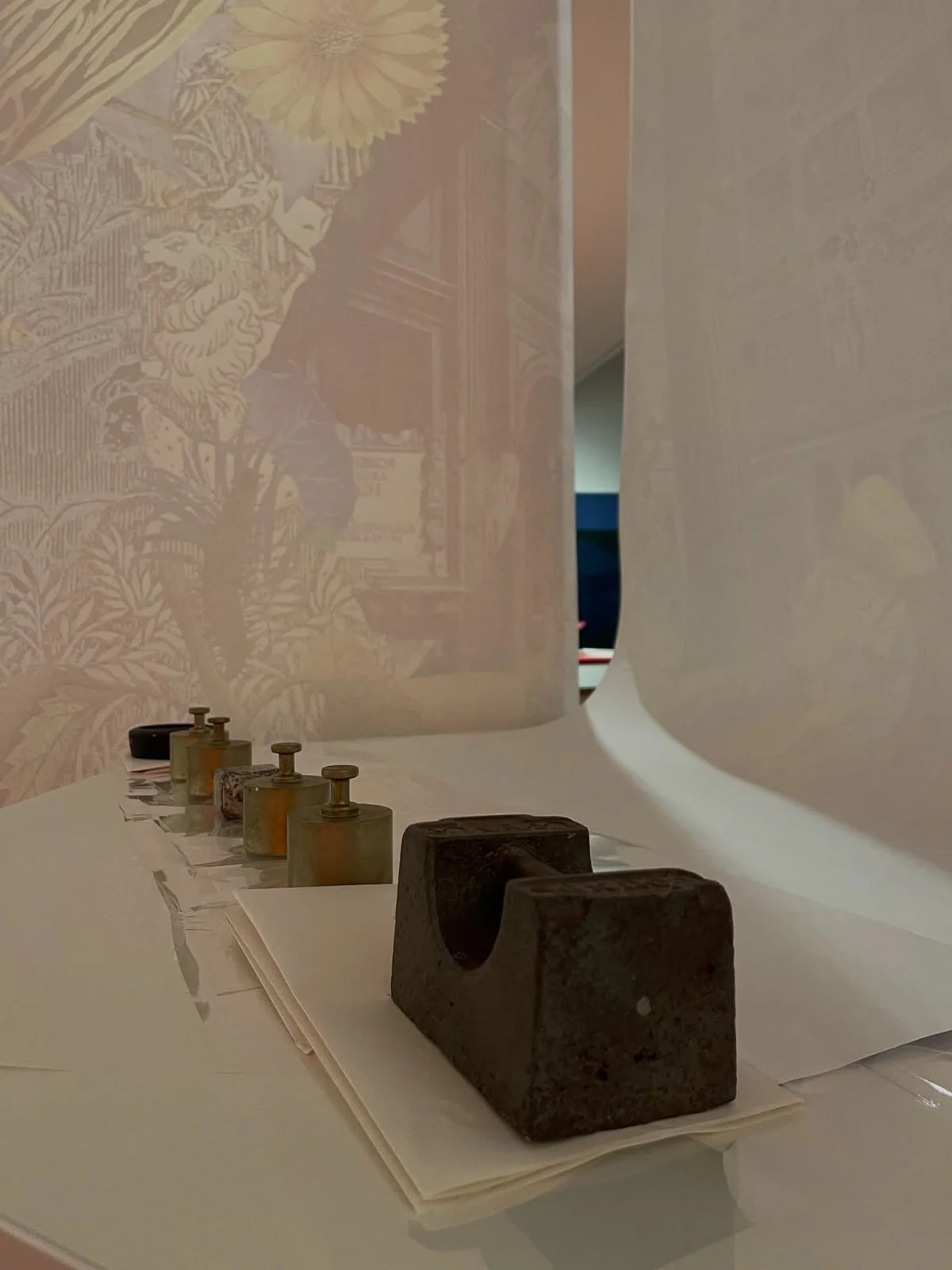

Such a task required a steady hand and precision. Overnight, beneath bookbinding weights and impromptu weights, they rested as they secured. Completed in pairs, owing to both space and availability of weights, they all but visually disappear, and remind us to always stay flexible in the installation process.

With the last two drops, having rested overnight, deemed ready for the weights to be removed and to join their companions, left and right, our collective shoulders can now drop away from the ears. Eight paper-wrapped aluminium batons now help tether the work, while still allowing it to hover from the floor and move as you walk past. It has been a moment to hold the breath as each baton was adhered, over three consecutive mornings, but now it is done.

A Velvet ant, a flower and a bird opens Thursday the 19th of February, 2026.

“The principal stressors underlying insect declines—land-use change (especially deforestation), climate change, agriculture, introduced species, nitrification, and pollution—are those also affecting other organisms. Locally and regionally, insects are challenged by additional stressors, such as insecticides, herbicides, urbanization, and light pollution.”

Related reading,

Wagner, David L.; Grames, Eliza. M.; Forister, Matthew L.; Berenbaum, May R.; Stopak, David, ’Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts’, , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (2) e2023989118, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023989118

Wehner, Rüdiger, ‘Polarized-Light Navigation by Insects’,‘Scientific American, Vol. 235, No. 1, 1976, pp. 106–115, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24950397

Image credit: Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison, detail of a draft of Specimen 1963, 2026, which features the composite image of a female Mutillidae, courtesy of Dr Ken Walker, Senior Curator of Entomology, Museums Victoria Research Institute, in a different position in the host’s nest, and other differences.